As she approaches her 96th Birthday in June, Grace Lee Boggs is a living legend. As a life-long politically engaged person, she certainly deserves the distinction, but not the assumption that sometimes trails that term – there is nothing nostalgic or static about Boggs. Her continuing involvement with current social change and her bold thinking about the history of social movements engage the reader of her new book, The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century (University of California Press), with critical insights throughout. This is hardly a book of stale phrases and empty bombast.

After receiving her Ph.D. in philosophy in 1940, a notable achievement for the daughter of a Chinese immigrant, Grace spent approximately ten years working within a circle of intellectuals associated with C.L.R. James. During this period she co-authored the essay Every Cook Can Govern, a still-relevant exposition of libertarian Marxism. In the early 50’s, as a labor activist, Grace moved to Detroit, a city then with a population of two million. In terms of per capita union membership, it was America’s largest proletarian city.

Shortly after moving she met and married an autoworker similarly engaged in revolutionary activity: James Boggs. James worked the assembly line at the gigantic Chrysler plant on the Eastside of Detroit; there he absorbed the reality around him and the ideas of the left-wing forces in the United Auto Workers. Grace called him an “organic intellectual” for his ability to learn from the entirety of his experiences and to see his role in a larger historic perspective. Grace learned her dialectical thinking at the university and James developed his “on the job” so to speak. Grace said that her partnership with Jimmy helped to make her a whole person.

When Grace settled in Detroit, it was at the apogee of its population. The decline of the city began after World War II, first with whites fleeing to the suburbs, and then with the exodus of autoworkers to the South and West, as automation began displacing jobs.

To James Boggs, the large scale introduction of automation in the auto plants precipitated the inevitable decline of the industrial proletariat. In the 60’s he published The American Revolution: Pages from a Negro Worker’s Notebook that critiqued some of Marx’s ideas as historically bound to a period of scarcity. We need – he was proposing fifty years ago! – to consider how we go about transforming a society that can create abundance. In other words, how do we direct technology to meet the needs of humankind?

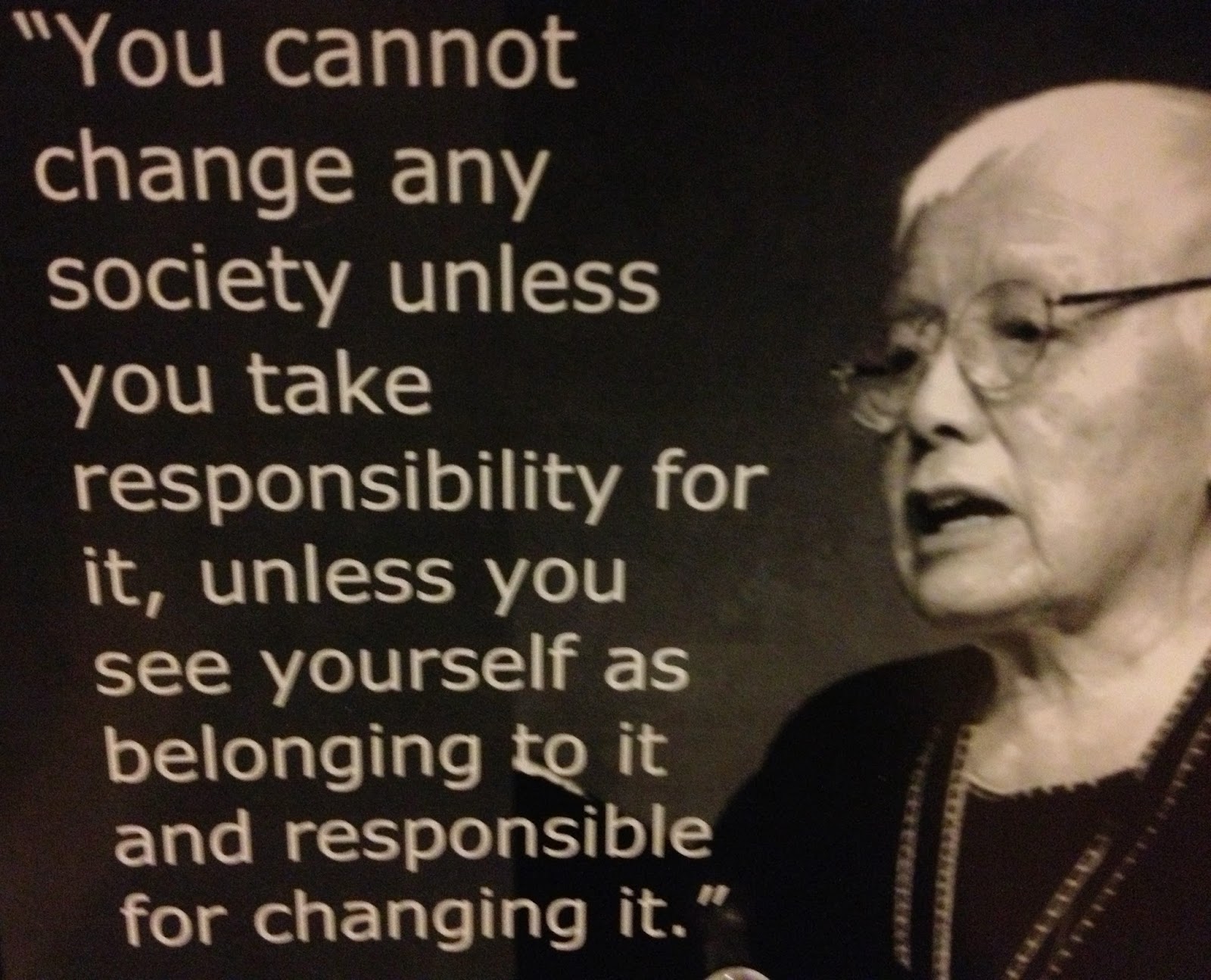

Grace Lee Boggs outlines this historic period briefly and then moves into the present. The book’s subtitle – Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-first Century – asserts her critical thinking about contemporary social change. As she states:

“.It has been my good fortune to have lived long enough to witness the death blow dealt to the illusion that unceasing technological innovations and economic growth can guarantee happiness and security to the citizens of our planet’s only superpower.”

The disappearance of millions of manufacturing jobs is a systemic occurrence and calls for full employment as a response don’t address the situation. Grace goes beyond the strategic criticisms of program to pose the overriding question of how do we define work today. Instead of proposals, for instance, like casinos that developers push with exaggerated claims of employment to mitigate the adverse affects on a community, Grace proposes grassroots development that serves community needs.

She sees the end of the industrial age therefore as potentially liberation, not disaster. Whole communities, she maintains, need the power to think creatively about their own best interests. One practical example of community creativity that Boggs relates from her experience is the expansion of urban agriculture. Community gardens, large and small, exist all over Detroit supplying food of course, but much more.

Boggs quotes Martin Luther King as saying that what we need in “our dying cities are ways to provide young people with … opportunities to engage in direct self-transforming and structure-transforming action.” Detroit’s community gardens with their hands-on approach develops self-reliance and fulfills King’s vision of community-linked learning ventures that teach life-affirming skills. When young people are respected for their contribution and freely participate in efforts that are immediately recognizable as socially useful, personalities are transformed and education begins. Besides, the whole process of gardening offers the opportunity for academic lessons in biology and physics that awaken student inquiry in a way not easily accomplished in the classroom setting.

Grace Boggs, referring to Gandhi’s teachings, recognizes two pillars to communities:

Work that preserves rather than destroys skills while fostering cooperation rather than competition and Education whose goal is the building of community rather than increasing the status and earning power of the individual.

The community-controlled projects in Detroit, like the gardens, confirm Boggs’ rejection of Cartesian rationalism, and its preference for calculation and a reductive interpretation of reality, from which flow all social engineering of both statist and neo-liberalist brands. She opts instead for a “knowledge that comes from the heart …[and] from relationships between people.”

For me, this is another way of saying that her philosophy issues from the practice of liberated social theory. What makes it liberated? My assumption is that our individuality plumbs its depths when we engage in activity that benefits both others and ourselves, so that sacrifice ceases to be the motivation for altruism, and is replaced by the desire to acknowledge our place in the community.

This book is rich in history, ideas and examples of innovative social projects. Boggs inspires without overstatement. The decades of experience behind her words are always tempered by humility, as when she traces her trajectory from early theories and activities to her present understandings.

That said, one wishes that she addressed at least one obvious question about “sustainable activism” – How can an alternative economy develop in a post-industrial world? We can’t base a future urban life on vegetable gardens alone; we can’t become the peaceful peasants that our rulers desire.

Boggs may suggest an answer in the chapter where she explores pioneering, sustainable projects from around the world. She mentions an architect who visited Detroit to demonstrate how to foster democratic urban architecture by incorporating local communities. His sessions brought together neighbors to propose designs for buildings that they could use. It seems possible to me that if architecture can arise (no pun intended) from the grassroots, then why not technology?

For example, urban agriculture on a scale larger than a garden plot, but smaller than a corporate farm, needs new kinds of tools – try to fit a standard commercial tractor on a city lot. Can these new tools be designed and manufactured on a local level? And what sort of engineering needs to be adapted to create sustainable greenhouses to grow produce year round in the cold climate of Detroit?

From urban gardeners to solar and wind engineers to barefoot architects to … what? The possibilities of new manufacturing require a fertile imagination and the recognition that some technologies can serve our needs; they can grow organically too.

Grace Lee Boggs offers a fitting conclusion: [Revolutions]… are about creating a new society in the places and spaces left vacant by the disintegration of the old; about evolving to a higher Humanity …”

After receiving her Ph.D. in philosophy in 1940, a notable achievement for the daughter of a Chinese immigrant, Grace spent approximately ten years working within a circle of intellectuals associated with C.L.R. James. During this period she co-authored the essay Every Cook Can Govern, a still-relevant exposition of libertarian Marxism. In the early 50’s, as a labor activist, Grace moved to Detroit, a city then with a population of two million. In terms of per capita union membership, it was America’s largest proletarian city.

Shortly after moving she met and married an autoworker similarly engaged in revolutionary activity: James Boggs. James worked the assembly line at the gigantic Chrysler plant on the Eastside of Detroit; there he absorbed the reality around him and the ideas of the left-wing forces in the United Auto Workers. Grace called him an “organic intellectual” for his ability to learn from the entirety of his experiences and to see his role in a larger historic perspective. Grace learned her dialectical thinking at the university and James developed his “on the job” so to speak. Grace said that her partnership with Jimmy helped to make her a whole person.

When Grace settled in Detroit, it was at the apogee of its population. The decline of the city began after World War II, first with whites fleeing to the suburbs, and then with the exodus of autoworkers to the South and West, as automation began displacing jobs.

To James Boggs, the large scale introduction of automation in the auto plants precipitated the inevitable decline of the industrial proletariat. In the 60’s he published The American Revolution: Pages from a Negro Worker’s Notebook that critiqued some of Marx’s ideas as historically bound to a period of scarcity. We need – he was proposing fifty years ago! – to consider how we go about transforming a society that can create abundance. In other words, how do we direct technology to meet the needs of humankind?

Grace Lee Boggs outlines this historic period briefly and then moves into the present. The book’s subtitle – Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-first Century – asserts her critical thinking about contemporary social change. As she states:

“.It has been my good fortune to have lived long enough to witness the death blow dealt to the illusion that unceasing technological innovations and economic growth can guarantee happiness and security to the citizens of our planet’s only superpower.”

The disappearance of millions of manufacturing jobs is a systemic occurrence and calls for full employment as a response don’t address the situation. Grace goes beyond the strategic criticisms of program to pose the overriding question of how do we define work today. Instead of proposals, for instance, like casinos that developers push with exaggerated claims of employment to mitigate the adverse affects on a community, Grace proposes grassroots development that serves community needs.

She sees the end of the industrial age therefore as potentially liberation, not disaster. Whole communities, she maintains, need the power to think creatively about their own best interests. One practical example of community creativity that Boggs relates from her experience is the expansion of urban agriculture. Community gardens, large and small, exist all over Detroit supplying food of course, but much more.

Boggs quotes Martin Luther King as saying that what we need in “our dying cities are ways to provide young people with … opportunities to engage in direct self-transforming and structure-transforming action.” Detroit’s community gardens with their hands-on approach develops self-reliance and fulfills King’s vision of community-linked learning ventures that teach life-affirming skills. When young people are respected for their contribution and freely participate in efforts that are immediately recognizable as socially useful, personalities are transformed and education begins. Besides, the whole process of gardening offers the opportunity for academic lessons in biology and physics that awaken student inquiry in a way not easily accomplished in the classroom setting.

Grace Boggs, referring to Gandhi’s teachings, recognizes two pillars to communities:

Work that preserves rather than destroys skills while fostering cooperation rather than competition and Education whose goal is the building of community rather than increasing the status and earning power of the individual.

The community-controlled projects in Detroit, like the gardens, confirm Boggs’ rejection of Cartesian rationalism, and its preference for calculation and a reductive interpretation of reality, from which flow all social engineering of both statist and neo-liberalist brands. She opts instead for a “knowledge that comes from the heart …[and] from relationships between people.”

For me, this is another way of saying that her philosophy issues from the practice of liberated social theory. What makes it liberated? My assumption is that our individuality plumbs its depths when we engage in activity that benefits both others and ourselves, so that sacrifice ceases to be the motivation for altruism, and is replaced by the desire to acknowledge our place in the community.

This book is rich in history, ideas and examples of innovative social projects. Boggs inspires without overstatement. The decades of experience behind her words are always tempered by humility, as when she traces her trajectory from early theories and activities to her present understandings.

That said, one wishes that she addressed at least one obvious question about “sustainable activism” – How can an alternative economy develop in a post-industrial world? We can’t base a future urban life on vegetable gardens alone; we can’t become the peaceful peasants that our rulers desire.

Boggs may suggest an answer in the chapter where she explores pioneering, sustainable projects from around the world. She mentions an architect who visited Detroit to demonstrate how to foster democratic urban architecture by incorporating local communities. His sessions brought together neighbors to propose designs for buildings that they could use. It seems possible to me that if architecture can arise (no pun intended) from the grassroots, then why not technology?

For example, urban agriculture on a scale larger than a garden plot, but smaller than a corporate farm, needs new kinds of tools – try to fit a standard commercial tractor on a city lot. Can these new tools be designed and manufactured on a local level? And what sort of engineering needs to be adapted to create sustainable greenhouses to grow produce year round in the cold climate of Detroit?

From urban gardeners to solar and wind engineers to barefoot architects to … what? The possibilities of new manufacturing require a fertile imagination and the recognition that some technologies can serve our needs; they can grow organically too.

Grace Lee Boggs offers a fitting conclusion: [Revolutions]… are about creating a new society in the places and spaces left vacant by the disintegration of the old; about evolving to a higher Humanity …”